The Life & Times of Dr. Robert Johnston

An exploration of one of Franklin County's most extraordinary sons.

By: Justin McHenry

The Johnstons of Antrim

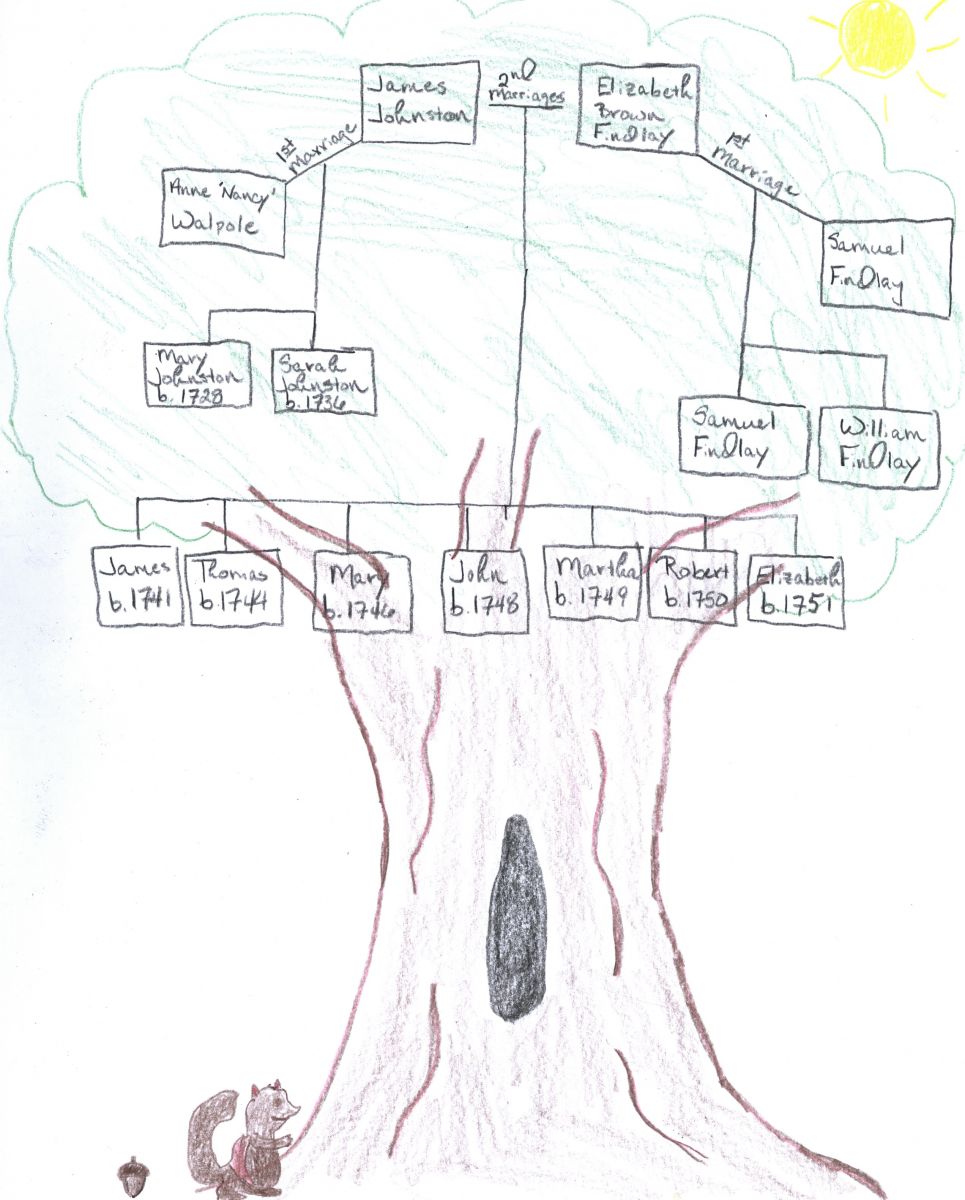

Robert Johnston was born into a convoluted family in the month of July in the year of 1750. He had half-sisters from his father’s first marriage. He had half-brothers from his mother’s first marriage. He had six brothers and sisters from his mom and dad.

James Johnston and his then wife, Anne “Nancy” Walpole, made their way to America from Ulster settling just north of Shady Grove in Antrim Township in 1735. They were some of the first European settlers of Antrim Township, which, at that time, was the western frontier of America.

Fun Family Facts:

Anne “Nancy” Walpole, James’ first wife, who passed away, was the daughter of Col. Robert Walpole, who was a prominent Whig politician in the late 17th Century and sired 19 children, the twelfth of which was Anne. Anne served as maid in waiting to Queen Caroline, wife of King George II. Anne’s brother, Robert, would go on to become Great Britain's first prime minister.

Elizabeth Brown Findlay was the daughter of Admiral James Brown. Admiral Brown was the Adjutant General for England during the Siege of Londonderry in 1688. He fled to America with his two daughters to avoid punishment relating to his service.

James, Robert’s brother, during the Revolutionary War, obtained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the Cumberland County Associators, serving with them from 1777 to 1782. He would go on to become Franklin County’s first representative to the State Legislature, serving from 1784-1785 and 1788-1793. He would also help Robert obtain cash while Robert was traipsing across Appalachia in search of ginseng.

Thomas Johnston, another one of Robert’s brothers, also served in the War, serving directly under Col. Abraham Smith in his battalion and under Gen. Anthony Wayne, for whom Waynesboro is named after. He was at the Paoli Massacre and by the end of the war had risen to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He was Franklin County’s State Senator from 1794-1803.

Like the Johnstons, many of these settlers were Scots-Irish. From 1710 to 1775, over 200,000 people of Scotch-Irish descent emigrated from Ulster to the American colonies. The majority of these settlers made their home in hills of Pennsylvania where land was cheap and plentiful, forging a new western frontier in America and creating a buffer for the colonies along the coast. By 1750, the Scotch-Irish were about a fourth of the population of Pennsylvania, rising to about a third by the 1770s. The typical migration involved small networks of related families who settled together, worshipped together, and intermarried. Life on the frontier was extremely challenging, but poverty and hardship were familiar to them. They would settle an area, work and cultivate the land, and build houses, mills, and settlements.

When the Johnstons settled the area in 1735, there was still a significant Native American presence in the Cumberland Valley. Up until the start of the French and Indian War in 1754, there were small Native American villages and settlements along the confluence of the branches of Conococheague Creek. The European settlers and the Native Americans lived in relative peace for many years, however, hostilities began to arise between the two in the early 1750s culminating in the French and Indian War, 1754-1763.

This was a brutal time for everybody on Pennsylvania’s western frontier. Raids by settlers and Native Americans alike were often vicious and deadly. The area’s population dropped from about 3,000 in 1755 at the start of the war to about 300, with most settlers not returning until after 1764 when the peace treaty was signed. Over 20 forts sprouted up around the area, built by settlers to offer collective protection from Native American raids. These forts include McCauley’s Fort near Greencastle, Allison’s Fort near Waynesboro, Chambers’ Fort present day Chambersburg, Sharp’s Fort, and Aull’s Fort.

This uncertain, violent atmosphere may have what led to Johnston going away to be educated in Philadelphia in an attempt to escape the worst of the fighting and violence taking place in the Cumberland Valley.*

*The most (in)famous bout of violence was the Enoch Brown School Massacre on July 26, 1764. On that day, four Delaware warriors entered a schoolhouse in Antrim Township, where they proceeded to shoot and scalp the schoolmaster, Enoch Brown, and started scalping the children. Brown and nine children were killed, two children survived their scalped wounds, and four children were taken as prisoners. At the time, Johnston was in Philadelphia working towards his Masters degree and teaching writing.

Boy Wonder

Robert Johnston was like a colonial Doogie Howser. At the age of 10, Johnston began attending the College of Philadelphia (the precursor to the University of Pennsylvania) most likely after finishing his secondary education at the Academy of Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin provided the guiding principle for both the Academy (kind of like a prep school for the college) and the College itself. Founded in 1749 by Franklin with the mission of providing a modern twist on classical education that stressed practical skills, the Academy of Philadelphia* would be far different from other colonial educational institutions, which sought primarily to educate and produce clergymen. Franklin and his Academy of Philadelphia was focused on preparing students for lives of business and public service.

*The College of Philadelphia would be chartered in 1755 and taken over by the state to turn into the University of the State of Pennsylvania in 1779 becoming in the process the first university in America and America’s first state school.

In all, there were nine colonial colleges: Harvard (founded 1636), College of William and Mary (f. 1693), Yale (f. 1701), College of New Jersey (would become Princeton, f. 1746), College of Philadelphia (f. 1749), King’s College (would become Columbia, f. 1754), College of Rhode Island (would become Brown, f. 1765), Queen’s College (would become Rutgers, f. 1766), and Dartmouth (f. 1769). All but the College of Philadelphia had some sort of sectarian affiliation.

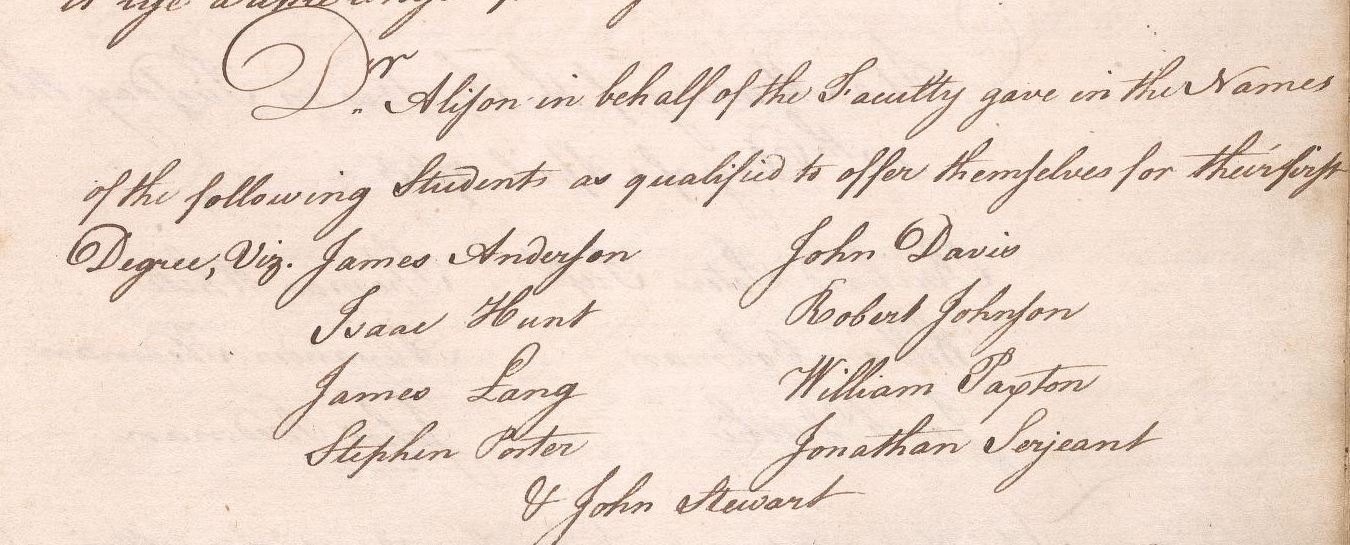

The age of students entering the Academy varied between seven to thirteen years of age and they spent several years honing their skills in a particular school (English, Mathematics, or Latin). Upon completion of Academy work, many students’ academic careers were over since at the time the overwhelming majority of careers and jobs did not require further study. A small group would continue on to the College, where a typical size of any given class year was in the teens with only a handful of those ever finishing their degrees. For example, there were nine who obtained their bachelor’s in Johnston graduating class in 1763 and there were none the following year. At the College, it generally took three years (freshman, junior and senior years) to earn a bachelor’s degree. A school year was broken down into three terms, and each term addressed a new unit and the courses included Latin and Greek, mathematics, natural science (called natural philosophy at the time), and moral history, which included ethics, oratory, logic, and history. It was the hope that at the end of three years of this diet of classes a student could apply independent thought to any of life’s challenges.

At the end of the three years, the students faced a public examination by members of the board of trustees, which, for Johnston, included people such as Richard Peters (close confidant of the Penns and who was President of the college at the time, as well as, Secretary of the Land Office for Pennsylvania), Jacob Duche, Sr. (former mayor of Philadelphia), and he was also quizzed by Ben Franklin himself.* Johnston’s examination took place in the Public Hall before a large crowd, and him and the rest of the students handled themselves well and passed. This led to a large, festive commencement ceremony filled with orations by members of the faculty and lots of musical interludes. Johnston would have been twelve at the time, his thirteenth birthday would be two months away.

*Can you imagine standing up in front of Benjamin Franklin, who even at that time was a larger than life presence in Philadelphia, and have him fire question after question at you mostly likely in Latin or Greek? And you had to answer him in either Latin or Greek.

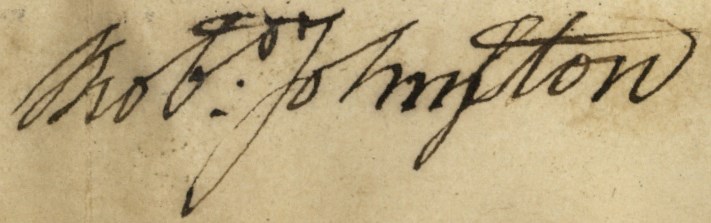

After graduation, Johnston continued on his education working towards a Masters of Arts, which he would receive in 1765 when he was fourteen years old. While in school for his Masters, Johnston served as a writing master at the Academy, instructing kids probably not much younger than himself on penmanship. He was such a good, dedicated instructor that the Board of Trustees in their meeting minutes twice called him out for his excellent work. First, in the trial period, they lauded the improvement in his students penmanship. Secondly, they actually thought enough of him to give him a raise for the time and effort he put in in the mornings in the summertime and after classes to make pens* for his students.

*Johnston spent his time making quill pens, which is an incredibly time-consuming effort. It involves a ten-step process to just prepare the quill and a second ten-step process to prepare the nibs. Here is a nice little article on pen making in Colonial America and also just what the duties of a writing master was at the time.

Johnston would stay on as a writing master at the Academy for the remainder of 1765. However, during that time, he became an apprentice of some sort somewhere in Philadelphia presumably. This apprenticeship was cutting into his teaching at the Academy and by the beginning of 1766, him and the Academy parted ways. It is not known where he was apprenticing. Since he would become a doctor, it may be a safe assumption to say he was apprenticing in the medical field somewhere in the city, which was the primary means of gaining a knowledge to become a doctor prior to the establishment of medical schools. Most surgeons apprenticed with a physician (an actual degree holder), butchers or dentists to learn their trade.

Multiple accounts have Johnston continuing his medical training in England. It was also not uncommon for a student to go to England (Oxford or Cambridge) or Scotland, as the University of Edinburgh had a renowned medical school, to get a degree to become a physician. There are no records though that state definitely that he did go abroad for more education.*

*The University of Edinburgh’s database of alumni does have a listing for a Robert Johnston who was there from 1770-1773. That is a common name and there isn’t any additional information to see if this is Franklin County’s Johnston. Though, the dates would match up with dates missing from Johnston’s timeline.

At the time Johnston was in Philadelphia gaining his education at the college, multiple advancements in the field of medical education were taking place. The College of Philadelphia was just getting America’s first medical school off the ground right after Johnston received his Masters. In addition, Dr. Thomas Bond, along with Benjamin Franklin founded the first hospital in America, the Pennsylvania Hospital.* The Hospital began admitting patients in 1756, and from the start it became a home to medical education. It also could have been where Johnston continued his medical education. A “Robert Johnson of Philadelphia” is listed as one of Dr. Bond’s clinical pupils from 1769.** Dr. Bond would later be one of a team of doctors to recommend Johnston for service as a surgeon during the Revolutionary War in 1776. This would denote some familiarity between the two, possibly obtained while Johnston was Bond’s pupil. The other doctors who recommended Johnston, Thomas Cadwalader, Adam Kuhn, and William Shippen, Jr., all have affiliations with either the College of Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Hospital, or both.

*The Pennsylvania Hospital is still operational and is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. It is the oldest hospital in America.

**Keep in mind that in all of the College of Philadelphia records Johnston is referred to as Johnson, and, if it is the same Johnston/Johnson, then he would have spent the majority of his life in Philadelphia. So he could easily have been Robert Johnson of Philadelphia.

Ol’ Sawbones

Upon completion of his medical education, by all accounts, Johnston came back to the Antrim Township and opened up a practice near Greencastle. He stayed there for a couple of years, seemingly content; however, with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775, him and his brothers headed the call and joined up to serve Pennsylvania and the American cause.

In late 1775, Drs. Thomas Cadwalader, Thomas Bond, Adam Kuhn, and William Shippen, Jr.* recommended the 25-year old Johnston for service in the Pennsylvania Militia. On January 16, 1776, Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety acted on that recommendation and appointed Johnston surgeon in Col. William Irvine’s Sixth Pennsylvania Battalion.

*The elderly Cadwalader was on a Committee with Drs. Bond and Benjamin Rush to examine Navy surgeon candidates. Bond helped organize the medical department for the Continental Army and set up the first field hospitals. Kuhn had Tory sympathies and when the British left Philadelphia so did he. He went down to the West Indies and stayed there for the duration of the war, returning to Philadelphia after the war to continue his academic career. Shippen had a long, rollercoaster-y career during the Revolutionary War. He began the war as the Chief Physician and Director General of the Hospital of the Continental Army in New Jersey. Then, he was made the Director General of the Hospitals West of the Hudson River. Finally, he arose to the position of Director of Hospitals for the Continental Army after a reorganization of the Army hospital system, and would be Johnston’s direct report when he became a Deputy Director. This was a position Johnston got primarily by playing politics and ousting former friend and colleague, Dr. John Morgan, whom he co-founded the College of Philadelphia’s medical school with in 1765. Morgan would level allegations of malpractice, misconduct, and misappropriation of funds at Shippen, who would go on to face a court-martial based on Morgan’s claims. Shippen was acquitted and returned to be elected Medical Director of the Army, but he resigned the post shortly after taking charge. Shippen was the brother of Edward Shippen III, the founder of Shippensburg.

Shortly after joining the Sixth PA Battalion, Gen. Washington ordered Irvine* to New York City and from there onto Albany and then eventually Canada. The Canada Campaign had begun the year before as a way to cut off one entry point for British forces coming into America and to put to rest any British recruitment efforts to get the Six Nations involved in the War. The First Continental Congress approved the plan of invading Canada (only Quebec would be invaded), and an invasion force under Gen. Philip Schulyer took off from Fort Ticonderoga and up Lake Champlain into Quebec. There was an engagement at St. Johns followed quickly by the taking of Montreal. From Montreal, the Continental Army, now under the command of Gen. Richard Montgomery, made its way to Quebec City. A second force sent by Washington under the command of Col. Benedict Arnold coming up through Maine met up with Montgomery on the Plains of Abraham in front of Quebec City, and promptly began besieging the city. The battle and siege were repelled, which started a retreat by American forces back down the St. Lawrence River. The Sixth Battalion arrived just in time to be thrust in as reinforcements during that retreat seeing its first action at the Battle of Trois-Rivieres.

*Irvine was himself a physician. Irish-born, he emigrated to America, settling in Carlisle. [Spoiler alert] He was captured at the Battle of Trois-Rivieres and held by the British for nearly two years before being exchanged for a British prisoner. Upon his release, he took command of the 7th PA Regiment and was promoted to Brigadier General in 1779. He went on to command Fort Pitt from the spring of 1782 to the Fall of 1783. Later he would serve as a member of the Continental Congress, 1787-1788, and a member of the 3rd Congress, 1793-1795.

The Americans had little intelligence on the terrain surrounding Trois-Rivieres, which meant that Brigadier General William Thompson led his force of 2,000 strong straight into a swamp on the outskirts of town. The battle did not go much better from there. When troops managed to make it out of the swamp, they faced either a formidable British force waiting them or a British warship firing grapeshot into them. So back into the swamp the Americans went. It was a disaster. Thompson and 17 of his officers, including Irvine were captured. Defeated at Trois-Rivieres, the Continental Army retreated South, out of Quebec, never to cross over into Canada again. The Army fell back to Fort Ticonderoga on the southern tip of Lake Champlain and that is where they wintered.

Johnston most likely was near the front receiving the wounded from his regiment. Director General of Hospitals, Dr. John Morgan (who recommended Johnston for service) had issued a set of regulations for regimental surgeons that included dressing wounded soldiers on a hill 3,000 to 5,000 yards to the rear of the battlefield, surgeons at these stations would only give emergency care only such as stop bleeding, remove foreign objects from the wound, apply dressings, reduce fractured bones. More serious operations such as amputations would take place either at the regimental or department hospital. Surgeons were also responsible for ensuring they received from the regimental leadership the appropriate transportation of the wounded off of the battlefield.

The Medical Department was kind of a mess and was never really straightened out during the duration of the war. There were rivalries between top officials (see Shippen v. Morgan). Every regiment had their own surgeons and tent hospital and had to scrounge around for provision for it. What organization there was had overlapping jurisdictions with no clear distinction on who was in charge of what. In February 1778, there was a reorganization of the Army’s hospital system in an effort to centralize the care of wounded or sick soldiers, by establishing a Director General in charge of all Hospitals in the Army and four Deputy Director Generals, each in charge of a different department (Northern, Eastern, Middle, and Southern). Head physicians and surgeons for each regiment within a department report to the Deputy Director. The Deputy Director can appoint Assistant Deputy Directors to handle the day to day operations of the Department’s hospitals: providing beds, furniture, utensils, hospitals, clothing, medicines, instruments, dressing, herbs, and other necessaries.

In January of 1777, Johnston began serving as a hospital physician and surgeon in the Northern Department, a position he would hold for the next year. The Continental Congress praised the work of the physicians and surgeons in New York following the retreat from Canada and the bitter winter of 1777, “The unremitting attention showed by Doctor Potts* and the officers of the hospital to the sick and wounded soldiers under their care is proof not only of their humanity, but also of their zeal in the preservation of the health and lives of the gallant asserters of their country’s cause.”

According to the National Archives, by the beginning of 1778, Johnston had been appointed Assistant Deputy Director of Hospitals in the Northern Department. In the same resolution that reorganized the structure of the Medical Department, Dr. Potts was transferred to the Middle Department as Deputy Director there. Congress passed along the Deputy Directorship in the Nothern Department to the “eldest” Assistant Deputy Director until further orders from Congress. Johnston apparently was the eldest Assistant Deputy Director at the time, and he assumed the role of Deputy Director for the Northern Department, which encompassed the part of New York north of the Hudson Highlands and Vermont.

With the surrender of a large British force at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, a major threat to the Northern Department was instantly wiped off of the map. The focus of the war shifted South and the Northern Department became relatively quiet. The British recruited Loyalists and loyal Native Americans to mount raiding parties on settlements and incite skirmishes around Upstate New York. Some of these skirmishes and raids were quite brutal in nature leading to many massacres on both sides. Maybe it is because the focus had shifted elsewhere that Congress did not think to appoint a new Deputy Director. Whatever the case, Johnston stayed up in New York performing his duties and as a result of his traveling between hospitals and commands, he was frequently used as a messenger, passing along letters from Gen. John Stark to Gen. Horatio Gates and letter and intelligence from Washington to Gen. Wayne.

By late 1780, Johnston was in South Carolina assisting with the treatment of wounded Americans captured by the British. The British had neglected in treating captured American soldiers leading to a dire situation for them. Chief Medical Officer of North Carolina’s militia, Hugh Williamson, a signer of the U.S. Constitution, received permission to go behind enemy lines to care for the sick and wounded. In a letter to the British Physician General and Inspector General of Hospitals of the in the Carolinas, Dr. John M. Hayes, Williamson wrote:

Our hospital patients are near 250, many of them dangerously wounded. They are lodged in six small wards, without straw or covering. Two of them have not any cloathing besides a shirt and pair of trowsers. In the six wards they have only 4 small Kettles, and no Canteen, Dish or Cup, or other Utensil. We have hardly any medicies and not an ounce of Lint, Tow, or Digestine, not a single Bandage or Poultice Cloath, nor an ounce of meal to be used for Poultices. In a word nothing is left for us but the painful Circumstances of viewing wretches who must soon perish if not soon relieved.

We were also weak in Medical Help. Our Militia Surgeons disappeared after the Battle and the Commander in Chief [Lord Cornwallis] had not yet turned his attention to the wounded Prisoners. It happened that one of the Continental Surgeons fell into the hands of the Enemy. It may be supposed that with his assistance, tho’ he was indefatigable, I found it impossible to give the desired help to 240 men who Laboured under at least 700 wounds. After three weeks we were happily reinforced by Dr. Johnson [Dr. Robert Johnston] a senior surgeon of great Skill and Humanity in the Continental Service.

In May of 1781, Johnston was officially made a physician and surgeon in the Southern Department. It is not known where Johnston was stationed at the time. He could have remained in South Carolina with Gen. Nathanael Greene’s force as it attempted to recapture the state from the British, ultimately succeeding in penning the British up at Charleston. Or he could have been with the Marquis de Lafayette to defend Virginia from Lord Cornwallis’s forces. This would ultimately end in Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1791. It has been passed down through the years that Johnston was at the surrender at Yorktown, but there is nothing that can substantiate that.

The day before the surrender which would all but end the Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress had appointed Johnston deputy purveyor for the military hospital of the Southern Department. He was put in charge of purchasing and acquiring all of the goods that the hospital may need from medicines and medical supplies to bedding and clothing.*

*He seemingly did all of the procuring of medicines and good on his own dime, travel costs as well. There are records from the Second Continental Congress discussing the bill Johnston submitted for costs of $1,600, which he paid out of pocket to secure the provisions needed. That would roughly equate to $40,000 today.

The British surrender at Yorktown effectively spelled the end of the Revolutionary War. British troops would remain in America for another two years until the Treaty of Paris could be signed that officially ended the war. During that time, the Continental Army shrunk with the lack of a threat.

Our Man in Canton

Nothing is known of Johnston’s whereabouts between October 1781 and August 1783. Congress greatly reduced the army hospital staff in July 1782 abolishing all together the offices of assistant apothecary and assistant purveyor. Perhaps he managed to stay on in some capacity with the waning war effort. Perhaps he resigned his post and went back home to Antrim Township.

In August of 1783, Johnston began his next adventure. He had been recruited by investors headed up by Robert Morris along with William Duer, John Holker, and Daniel Parker in a scheme to open up China to American trade. He would be the investors ginseng broker, and he was given three months to scrounge up as much ginseng from the backcountry as possible.

.jpg)

The Chinese wanted ginseng. They couldn’t get enough of it. Ginseng has a long tradition in Chinese preventive and restorative medicine, and was used for a wide variety of treatments for cancers, rheumatism, diabetes, sexual dysfunction, and aging. The plant grew wild and in abundance in the Appalachians. In ginseng, the investors had found their premier trading good. They believed they could have gotten up to $15 per pound for the plant (they ended up getting closer to $5/pound), which would garner them 500-600 percent profit. It was a very appealing prospect.

Johnston may have been uniquely qualified to perform the duties of ginseng wrangler. Having been born on the Pennsylvania frontier and the very eastern edge of the Appalachians, Johnston had some familiarity with the types of people and places he’ll be traveling and running into. Also, as a assistant deputy director and deputy purveyor during the war, he received unmeasurable on the job training in obtaining supplies, buying on credit, and locating hard to find basics needed to keep the hospitals under his command functioning at a high level as long as possible. A lot of it was about making quick relationships and getting what you need from them. Johnston was described as “a Man possessing a very Noble and Philanthropic mind”, which would go a long way towards ensuring he locates enough ginseng to make the voyage profitable.

He became an agent for Turnbull, Marmie & Co., who were tasked with procuring the ginseng for the trip on the Empress of China, the boat making the trip to China. With a thousand dollars in his pocket, his long and winding journey began in Philadelphia on September 3, 1783 where he set off for Fort Pitt (modern day Pittsburgh). He reached the Fort in about a week’s time and almost immediately headed south reaching Bath, VA on September 12th. A journey that would have taken him along and over some of the most rugged terrain in the Ridge and Valley section of the Appalachians. From Bath, he sent off a report back to Turnbull, Marmie, & Co.:

After a most tiresome Journey across the Frontier of Pennsylvania, yesterday I arrived at Bath in Virginia: as yet my success has not been equal to my Expectations. I have not been able to procure more than 400 weight of Ginseng on my way to this Place for which I gave 3s/9d pr. lb.

I have adopted such Measures as I think will secure all that may come down from the back woods between this & the 1st of Novr at the same rate.

I am informed that large Quantities has passed on to Baltimore & Alexandria within this Month. I would advise you to employ some Person to secure that which may have gone to those Places: I fear it will not be in my power to provide to Quantity wanted, the Season being so far advanced.

I have got the promise of 2000 weight to be delivered to me in Cumberland on or before the 14th of October at 3s/9d p lb. Also, I am promised about 1500 weight to be delivered at this place for 3s per lb. I will want about Two Thousand Dollars in Cash on or before the 14th of Octr.

I have a Brother in the Assembly (James) to whom I have wrote & enclosed an Order in his Favor...for Two Thousand Dollars which Sum if you can give to him in Gold there will be no doubt of my getting it safe, in proper time - He will deliver you this letter. Bank Notes will not do in these parts. I have got 500 Dollars of them. The Country People will not receive them, neither can I get Store keepers to exchange them. Tomorrow I set out for Stantown (Staunton) and Augusta, where I am informed large Quantities of Ginseng has been sent from the Frontier parts of the State. (*The transcription of this letter and any of letter from Johnston to his bosses comes Philip Chadwick Foster Smith’s The Empress of China, Smith book on the voyage. It is exhaustively researched and contains a wealth of great information.)

Johnston kept right on travelling. He returned to Philadelphia and reported directly to Turnbull, Marmie & Co. and then almost immediately headed to New York to meet with the financiers of the Empress. His biggest obstacle was not so much the traveling and securing of ginseng it was finding enough cash to pay for it all. As he said in the above letter “Bank Notes will not do in these parts” only cash will suffice and the financial backers of the venture weren’t forthcoming with actual cash.

He travelled again throughout all of October and on into November into the backcountry of Virginia obtaining more and more ginseng, back to Philadelphia and New York, on to Franklin County. At the same time, he was working on getting that ginseng sent up to New York and packed away into the awaiting Empress. More than 30 tons in fact made its way between mid-November and mid-December. When all was said and done and the Empress of China finally set sail on February 22, 1784, it had in its hold 57,687 pounds of ginseng.

Johnston decided he was not yet done travelling and signed on to be the Empress of China’s surgeon.* Johnston’s duties would be rather light than what he was used to as a surgeon during the war. On a trading vessel, he was responsible for seeing to any sick sailors or any injuries that should arise. He also had to ensure that all the men received proper nutrition to prevent diseases from breaking out. There are only a handful of mentions throughout the Captain’s log (what portion we have of it) that reference sick or injured sailors where Johnston would have to attend to them, and there were most likely other smaller injuries (cuts, scrapes, bruises) that he would see to that did not merit any mention at all.

*If you haven’t done so already, do yourself a favor a read the Aubrey/Maturin series of books by Patrick O’Brian. Not only does it provide a great glimpse at what life was like for a surgeon on the open seas in the same general timeframe, they’re just really good, fun books to read. Also, while you’re at it, go watch Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, an excellent adaptation of two of the books directed by acclaimed Australian director Peter Weir and which stars Russell Crowe as Capt. Jack Aubrey and Paul Bettany as Dr. Stephen Maturin, the ship’s surgeon.

All in all for a journey halfway around the world and back and America’s first time trading with China, it was uneventful. After about a month at sea, the Empress stopped at the Cape Verde Islands a couple hundred miles off the coast of Africa to replenish their fresh water supply. Johnston got off and did a little bird hunting. Once back out to sea, it would be nearly four months till they next time they spotted land. They sailed down Africa and rounded the Cape heading out into the Indian Ocean finally sighting Java on July 17th. While at Java, Johnston would explore the Island and visit a few local villages. There the Empress fell in line with a large French trading vessel, Triton, and the two sailed on to Canton (modern day Guangzhou).

Indirectly, China played a role in the Revolutionary War. It was Chinese tea that was dumped in the harbor at the Boston Tea Party. Tea itself had become a staple in the colonies, and finding a direct means of procuring it was of great import. The Empress would fill its hull on its return voyage with the same kind of teas that got tossed into Boston harbor. France also, in part, joined the war on the American side to fight against a British monopoly on trade with China.

The Empress would stay four months in Canton. Foreigners were confined as to where they could go in Canton itself, what amounted to a few blocks. So the crew’s time in Canton seems rather pedestrian and boring. There were some socializing with other officers from other ships and Chinese merchants working in the foreign zone, but, for the most part, everybody kind kept to themselves. All passengers found the time to buy goods such as porcelain items and silk goods. A few accounts state that Johnston brought back such goods along with a Chinese manservant. On January 12, 1785, the Empress of China set sail for America docking in New York on May 11, 1785. The return trip was mostly harmless.

Landed Gentry

Back on terra firma, Johnston returned to the newly formed Franklin County. Yet he remained quite active even in national events up until his death in 1808. During the remaining years of his life, he did amass a wealth of land all across Franklin County. Go on the Archives’ online repository, and there is references to land he owned in Antrim, Montgomery, Guilford, Washington, Southampton, Warren, Peters, and Quincy Townships. In the 1796 Tax Assessment, he was taxed for 1,000 acres in Antrim Township alone and close to 500 acres in Washington Township alone. He had settled into a role of a landed gentry in Franklin County, building a sizeable home a couple miles south of Greencastle. He owned slaves, as many as seven. Cows. Horses. Deer.* Mills. Distilleries.

*Deer parks were a thing in Colonial and Early Republican times. Some landowners fenced in an area and kept deer in there much like cows to use as a readymade supply of venison. Others just kept and tamed deers for the social status of it all, as many prominent men of the day built deer parks on their estates. For example, George Washington maintained a deer park on the grounds of Mount Vernon, and friends and well-wishers often gave him deer as presents.

178?

Though it is not known when they married, Johnston wed Eleanor Pawling at some point most likely after his return from China. Pawling herself had an interesting life up to that point. Her father was Henry Pawling, owner/operator of Pawling’s Tavern. The tavern was a common rest point on the King’s Highway, which connected the Susquehanna and Potomac Rivers. It was also at the crossroads for wagons traveling west. The pack train that set off Smith’s Rebellion in 1765 stopped at Pawlings. Eleanor was a student of Enoch Brown and for whatever reason missed school on the day of the massacre. She was a rather rotund lady, up to 400 pounds by some account. She owned the first carriage in Franklin County, and was said to be a “great force of character.” The couple never had children, but they did adopt Johnston’s sister’s youngest son, John Boggs, who would go on to become a physician himself in Greencastle.

1786

He was made professor of mathematics at Dickinson College. He also taught general science and natural philosophy there. It is not known how long he taught there, but he did leave $50 to Dickinson in his will.

Dickinson College was the brainchild of Benjamin Rush, doctor, signer of the Declaration of Independence and recommender of Johnston to become a regimental surgeon. He wanted a college set on the frontier, and chose Carlisle, there was a grammar school already located there that would serve as the College’s foundation, as the ideal place for a new college. The school was chartered in 1783, and the board of trustees first met in 1784, where they selected Dr. Charles Nisbet to be the college’s first president. Johnston would serve as the school’s first mathematics professor.

1787

Friend and fellow Revolutionary War surgeon, Barnabas Binney, father of Horace Binney, dies while visiting Johnston at his home. Johnston embalms his friend, which is widely considered to be the first embalming done in Franklin County. Some claimed it was a rare in that day and age, which it was for Franklin County, but embalming was a known practice in more heavily populated areas such as Philadelphia. It was claimed he learned how to embalm while in China, though he most likely learned it while continuing his studies in England, where it was being taught at the time.

1790

Unsuccessfully ran for State Senator from Franklin County losing to Abraham Smith.* As a consolation, he was appointed collector of excise for Franklin County. Excise collector was a brand new position created out of a need by Congress to start paying off war debts. This led to the passage of the first national internal revenue tax. A new tax was levied against distilled spirits, a whiskey tax. This was a huge deal for small farmers, isolated on the frontier away from easy means of transportation to markets. So come harvest time when the grain is all collected, surplus grain was distilled into whiskey, which was easily stored and transportable. In addition, whiskey served as a kind of currency in the west. With the lack of a standard currency or banks for that matter issuing bank notes, whiskey was the next best thing. Now the government was not only taxing their livelihood but also requesting they pay cash for the tax, something they didn’t necessarily have. This was met with great consternation particularly in the western counties of Pennsylvania. Collectors were beaten, tarred and feathered, and faced constant threat of violence.** Johnston seems to have escaped all of that during his time as a collector. Maybe due to his stature within the community and his personal relationships with many in Franklin County, or maybe the whiskey makers of Franklin County did not face the type of hardships plaguing those in the west, whatever the case may be, Johnston performed his duties without the slightest hint of controversy.

*Abraham Smith actually served with Johnston as part of Col. Irvine’s battalion, receiving his commission a week before Johnston.

**Allegheny County’s collector was Robert Johnson, which makes researching our Johnston extremely confusing, but the Allegheny Johnson had the unfortunate distinction of being the collector most abused by the locals.

1792

Elected as a Presidential/Vice Presidential Elector. Since in 1792, it was all but a forgone conclusion that George Washington was going to be elected President, the electors that year basically just voted for Vice President. In a letter to John Quincey Adams, John Adams states that he received all but one of the electors votes for Vice President. That one dissent being Robert Johnston. It is not known who Johnston did vote for to be Vice President. New York Governor George Clinton (50), Thomas Jefferson (4) and Aaron Burr (1) were the only other people to receive electoral college votes. Johnston served alongside Clinton while in New York, and he apparently had some sort of relationship with Thomas Jefferson (it’s been passed down that Jefferson was a visitor to his house in Antrim Township and Jefferson would appoint Johnston tax collector during his term in office). So the safe money is on him voting for either of those two.

1794

George Washington on his way to quell the Whiskey Rebellion stops over at Johnston’s home and spends the day at his house.

What started in 1790 with the collection of the Excise Tax kept building and building over the years until there was outright rebellion in western Pennsylvania. When U.S. Marshals appeared in Southwestern Pennsylvania to serve papers to those who did not pay the tax to appear in federal court in Philadelphia, the organized rebellion began in earnest. In response to the rebellion percolating in the western counties, 13,000 militiamen gathered at Carlisle. Washington would ride out to Carlisle to take command of that force (during which he visited Johnston). He marched the force to Bedford where he passed over command to General Henry "Lighthorse" Lee, father of Robert E. Lee, who moved the militia force into western Pennsylvania and proceeded to arrest the leaders of the rebellion ending the violent opposition to the Whiskey Tax. Political opposition still remained and with the election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800, the Excise Tax was repealed in 1802.

1800

Made Tax Collector for Western Pennsylvania by Thomas Jefferson. This would have been an easier job than what it appears to be, since Jefferson despised direct taxation of the people and actively worked towards abolishing all internal taxes. Under Jefferson, the government would be financed primarily through the sale of public lands and customs duties.

1802

Col. Edward Bartholomew, who was married to a Rachel Pauling so he might have been distantly related to Eleanor, is accidently shot by his son-in-law, Jonathan Henderson of Huntingdon, while at Johnston’s house.

1807

He was made a Major-General in the Pennsylvania Militia. At the time, militias served as like a National Guard for the state, in fact by the 1870s, the state’s militia will be rebranded as the National Guard of Pennsylvania. Militias not only formed to protect and serve the state, but also served as America’s military reserve force should it find itself at war again like it will in 1812. At the time, there was a compulsory requirement that men of a certain age had to serve in the Pennsylvania militia. Though by the early 1800s, the militia was in disarray. Recruits weren’t showing up for training, and there was a glut of high-ranking officials but with little system in place to organize the whole shebang. So Johnston’s appointment at the time was mostly likely ceremonial rather something resembling an actual command.

Johnston died on November 25, 1808. He was 58 years old. He’s buried beside his father and wife at the Cedar Hill Cemetery outside of Greencastle. His was a full life to say the least. Not many can boast of the experiences and adventures he got live, which took him to the other side of the world and have him brushing shoulders with the fathers of our nation: Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, etc. He was a man of substance and truly one of the greatest Franklin Countians.

You can find a wealth of documents relating to Robert Johnston in the Archives’ online repository.

References

I used a wide variety of sources to put this post together and tried to provide direct links to the actual source material throughout the post. Otherwise, below you’ll find a summation of the sources used to tell Dr. Johnston’s story.

The Johnstons of Antrim

Two articles in particular were a huge help in not only piecing together the Johnston family tree but also give a sense of what life was like in the early settlement days of Antrim Township, Sidney Nill’s On Conococheague Settlement, 1732-1782 and Calvin B. Bricker’s Notes on the Early History Along the Conococheague Creek in Antrim Township, Franklin County, Pennsylvania.

Boy Wonder

The University of Pennsylvania’s Archives website is actually a treasure trove of information regarding to Penn’s history at the time Johnston went there. Not only did it provide great background information, they have made available a number of source material, where I was able to track Johnston’s academic life from 1760 to 1765. Examples of which can be found here, here, here, here, and here. There’s a lot more actually, and I particularly enjoyed the quite detailed description of Johnston’s graduation ceremony for when he received his Masters degree (here and here).

The Rehoboth Journal had a nice, informative article on colonial era higher education that helped fill in the context for what was happening in America in regards to colleges at the time.

Ol’ Sawbones

There were a few articles that helped to provide valuable information on the role of Revolutionary War surgeon and what the function of the hospitals were during the war: L. G. Eichner’s The Military Practice of Medicine During the Revolutionary War, a series of blog posts by Brian Altonen entitled Revolutionary War Doctor, and Medical Men in the American Revolution by Louis C. Duncan.

Documents relating to Dr. Johnston’s actual service during the War comes from a couple different sources. Primarily, the National Archives’ Founders Online site, which has a collection of documents from George Washington, Ben Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. Examples of correspondence regarding Johnston can be found here and here. The Library of Congress has made available online the Journals of the Continental Congress, which provided details on him being made a surgeon at the hospitals and other assignments.

If you’re interested in a good read about America’s invasion of Quebec and it’s attempt to conquer Canada, then I’d suggest Mark R. Anderson’s The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony.

Our Man in Canton

Philip Chadwick Foster Smith literally wrote the book on The Empress of China. While there are some other accounts of the voyage, they all either pale in comparison to Smith’s research or just rip-offs of it. I definitely ripped off from him. If you’re looking for a general overview of Sino-American relations up to around the Civil War, then Eric Jay Dolin’s When America First Met China is a very engrossing history that includes a sizable bit on the Empress of China.

Landed Gentry

Information regarding the founding of Dickinson College comes from Dickinson College itself. The Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau has a really nice little write up on the Whiskey Rebellion on its website, and that provided the bulk of the background information concerning that time period. Joseph J. Holmes’s article, The Decline of the Pennsylvania Militia, 1815-1870, from the Pennsylvania Historical Magazine offered valuable insight into the Pennsylvania Militia at the time Johnston was made Major General. Other information was gathered from newspapers from the period.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)